The 1992 presidential race was contentious. President George H.W. Bush was an incumbent, World War II veteran, and former two-term Vice President running in the face of challenging economic circumstances and the perception that he’d “betrayed” some of the promises he’d made as a candidate (“read my lips: no new taxes”). Bill Clinton was an upstart Governor from Arkansas, only 45 years old, and a “new” Democrat with heterodox views on things like crime, welfare, and budget. When Clinton entered the race, Bush looked unbeatable. He was not. The campaigns had all the mudslinging and dirty tricks one might expect. Ultimately Clinton won the presidency with 43% of the popular vote and 370 electoral votes.

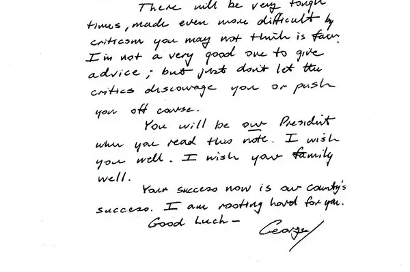

There must be few things as disappointing as losing the presidency. The ideological divide between Clinton and Bush was wide. They represented different visions of the world, generations, and governing philosophies. They had battled vigorously for the most important job in the world. So, it must have been a surprise to President Clinton when he found the following note waiting for him on his first day in office:

What a remarkable show of empathy from the one of the only men who truly could relate to Clinton’s experience. Decades later, the note still moved Clinton deeply. Over time, these two fierce ideological and political opponents developed an authentic friendship. It solidified as the two traveled the world together in the wake of a devastating 2004 Tsunami and in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. In many ways Bush became the father the Clinton always lacked. Years later, when I met both through the Presidential Leadership Scholars, Clinton teared up speaking of Bush as a friend and mentor. They never agreed on everything. But they cared for one another and worked together where they could.

Ideologically diverse relationships are nothing new. President Reagan and Tip O’Neill had a famously warm relationship. Professor Robbie George and Cornell West toured the country speaking together about their differences. Henry Fonda and Jimmy Stewart were close compatriots. And even Hunter S. Thompson and Pat Buchanan found a way to be friends.

Unfortunately, we seem to be losing this capacity for friendship and empathy across ideological lines. The internet and social media have pushed us into political and philosophical bubbles. Those virtual bubbles are migrating into the real world, as people increasingly move physical homes to live among their philosophical allies—leading to increasingly polarized Congressional districts. And we are more politically and ideologically divided than at any point in recent history, in a world in which isolation, fear, and anger are increasing as well. These divides cause us to caricature and loathe one another. And they cause us to develop ever-more extreme and difficult to reconcile political beliefs.

I certainly see this in my own life. I have fewer opportunities to interact with those with radically different political, cultural, or religious positions. I find it harder to understand how anyone could disagree with my ideas. More than I want to admit, I demonize those with whom I have deep disagreements—believing the worst of them and the best of me.

We need strong beliefs. As a person of faith, I hold certain truths dearly. Politically and culturally, I have strong opinions about the way to structure government and society to create flourishing. I believe I have an obligation to myself and others to be principled advocate for those beliefs.

But my faith and philosophy also teach me humility—that while truth is objective, my ability to fully perceive and interpret that truth is limited. They teach me to love others, particularly my “enemies,” since everyone I encounter is made in God’s image, possessed of inherent dignity and worth. They teach me that power corrupts, that no one person can or should be trusted with it, and that tensions and disagreements in a political system ultimately guard against the most dangerous tendencies of government. And they tell me that it’s only through the civil exchange of competing ideas, and the open-mindedness to take those ideas seriously, that we can collectively draw closer to truth. I worry that if I and others lose sight of these practices, we may lose both our humanity and our capacity to perpetuate this beautiful experiment in self-governance we call the United States.

There’s no mechanical solution. We shouldn’t force people to live in ideologically diverse communities. While we can make structural changes to things like districting or committee assignments that might make Congress more functional, there’s no silver bullet for the fundamental divides that have emerged among our representatives and communities. We can’t and shouldn’t force media to be “fairer”—history has taught us how fraught that becomes.

Rather the solution is deeply personal and cultural. It’s believing the best, not worst, of those we encounter. It’s taking the time to become informed, and showing curiosity about the world around us. It’s authentically seeking out and giving grace to those who think differently than us—much as George H.W. Bush did. Its guarding against the temptation to make every disagreement a matter of good and evil, life or death. It’s moderating rhetoric, particularly rhetoric that might inspire others to violence, instead speaking “truth in love.” And it’s seeking to live more humbly, justly, and mercifully towards everyone with whom we interact even as we advocate forcefully for those things we believe.

Our divisions are real. Some things worth fighting about and for. But our Democracy and way of life won’t persist if our culture becomes too degraded and divided to function. As we endure yet another contentious moment in American politics, it may be more important than ever to embrace friendship across our divides, to thoughtfully consider the opinions of other, and to exercise a balance of conviction and humility in how we relate.

John Coleman leads an investment firm and is the author of The HBR Guide to Crafting Your Purpose. You can follow his writing at

.

I’ve always loved this letter. Completely agree with your points as well. Remind me to tell you about my friend Sis some time.